Pioneering Women - Marie Tharp

Marie Tharp was an American oceanographer, geologist and cartographer whose work was instrumental in creating the first global map of the ocean floor. Her work proved that the seabed was not flat and featureless, as many believed at the time.

Marie was born in Michigan, U.S. in 1920. Her father, William, worked as a surveyor for the United States Department of Agriculture, collecting soil samples and rocks to create soil maps from all across the country. In Marie’s own words ‘by the time I finished high school I had attended nearly two dozen schools and I had seen a lot of different landscapes. I guess I had map-making in my blood, though I hadn’t planned to follow in my father’s footsteps.’ She graduated from university with a music and english degree, still unsure she had found her passion. The United States’ entry into WWII, however, led to a rare chance for women to study a degree in petroleum geology. Marie earned her Master’s in Geology in 1944 and a further bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1948, after which she became a research assistant at the Lamont Geological Laboratory at Colombia University, where she met Bruce Heezen, who she would work with over the next 30 years.

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

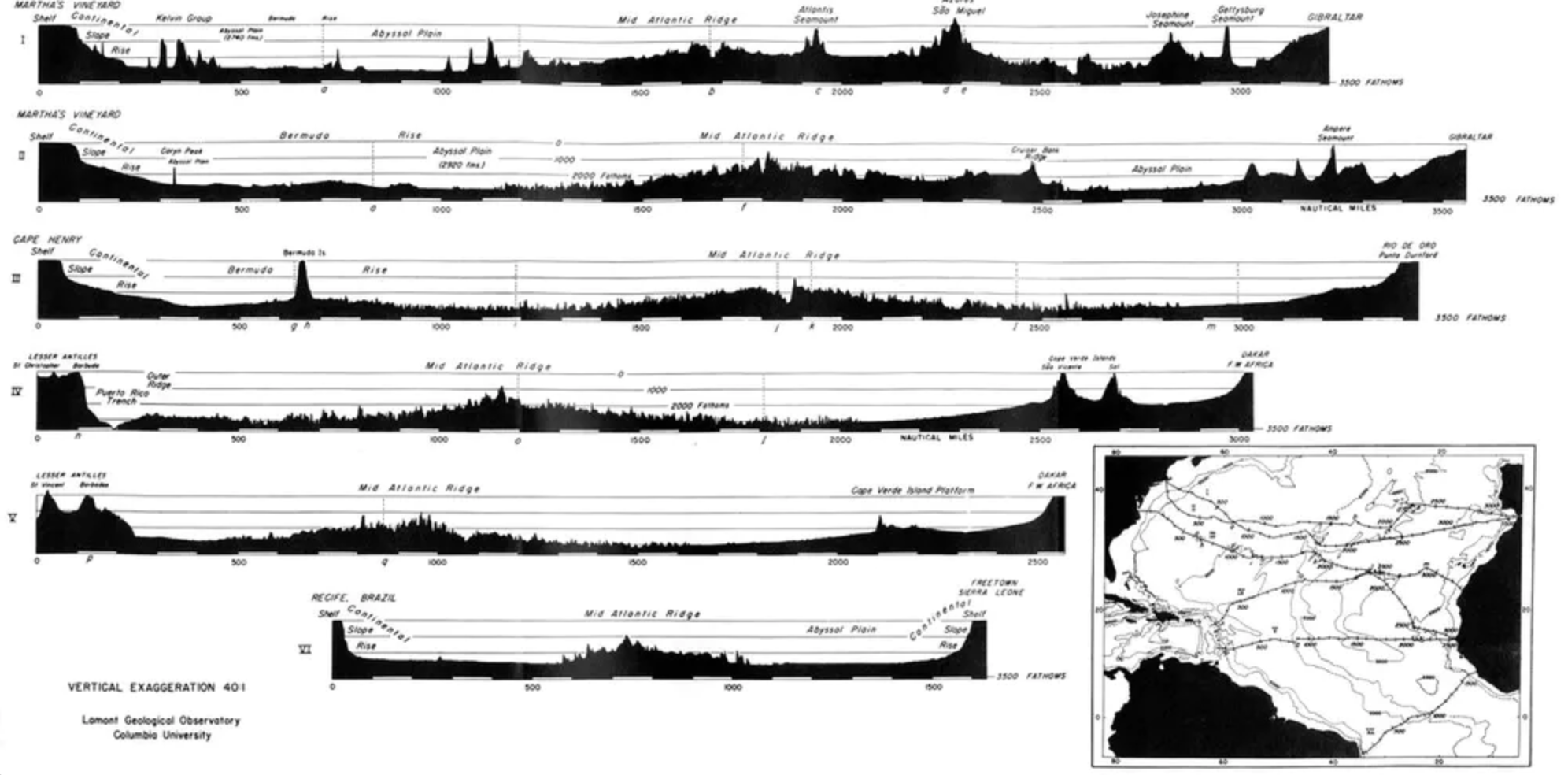

In the 1950s the U.S. navy was interested in mapping the ocean floor. Marie and Bruce began their research project to map its topography. Marie, as a woman, however, was not allowed onboard the research vessels. Bruce collected the raw data from offshore, which came from SONAR measurements, and sent it back to Marie. She collated the information and drew by hand, starting with a large sheet of blank paper, the lines of latitude and longitude and the location of each sonar profile. Her detailed plotting revealed a wide and deep rift. Bruce and other scientists were sceptical, telling her “It cannot be. It looks too much like continental drift,” a theory dismissed as almost impossible at the time. Marie was told to redraft. The rift appeared again. Marie and another research assistant noted that the rift was the epicentre for several earthquakes. This was a key and revolutionary development in plate tectonic theory, suggesting that continents could in fact be moving apart.

Marie’s first hand drawn map of the North Atlantic ocean floor was released in 1957, revealing underwater canyons, ridges and mountains. By 1977 Marie completed a full map of the world’s ocean beds, called The World Ocean Floor.

Lamont Geological Observatory, Colombia University

As a female scientist, Marie oftentimes struggled with the scientific community crediting her work and ideas. However, in 1978 the National Geographic Society awarded her their highest honour, Ernest Shackleton and Jane Goodall among other recipients of the award, and in 1996 she received an Outstanding Achievement Award from the Society of Women Geographers and was recognised by the Library of Congress’ Phillips Society in 1997 as one the 20th Century’s Outstanding Cartographers. Marie passed away at the age of 86 in 2006. Today she is recognised as pioneer in a male dominated field - she was critical in illuminating a before unknown world. Marie Tharp’s work is fundamental in modern geology.

“Not too many people can say this about their lives: The whole world was spread out before me (or at least, the 70 percent of it covered by oceans).I had a blank canvas to fill with extraordinary possibilities, a fascinating jigsaw puzzle to piece together: mapping the world’s vast hidden seafloor. It was a once-in-a-lifetime—a once-in-the-history-of-the-world—opportunity for anyone, but especially for a woman in the 1940s. The nature of the times, the state of the science, and events large and small, logical and illogical, combined to make it all happen.”

Marie Tharp in July 2021. Bruce Gilbert, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

“I think our maps contributed to a revolution in geological thinking, which is some ways compares to the Copernican revolution. Scientists and the general public got their first relatively realistic image of a vast part of the planet that they could never see. The maps received wide coverage and were widely circulated. They brought the theory of continental drift within the realm of rational speculation. You could see the worldwide mid-ocean ridge and you could see that it coincided with earthquakes. The borders of the plates took shape, leading rapidly to the more comprehensive theory of plate tectonics.

I worked in the background for most of my career as a scientist, but I have absolutely no resentments. I thought I was lucky to have a job that was so interesting. Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge that went all the way around the world for 40,000 miles—that was something important. You could only do that once. You can’t find anything bigger than that, at least on this planet.”

‘Connect the Dots: Mapping the Seafloor and Discovering the Mid-ocean Ridge'by Marie Tharp, April 1999